Seeing through the Tyrant's I

How the grammar of tyranny helps explain Trump’s conception of power

Tyrants rule in the first person. The tyrant sees the world as the product of his all-powerful “I.” The tyrant says “I alone decide,” “L'état, c'est moi,” or “I am the state.”

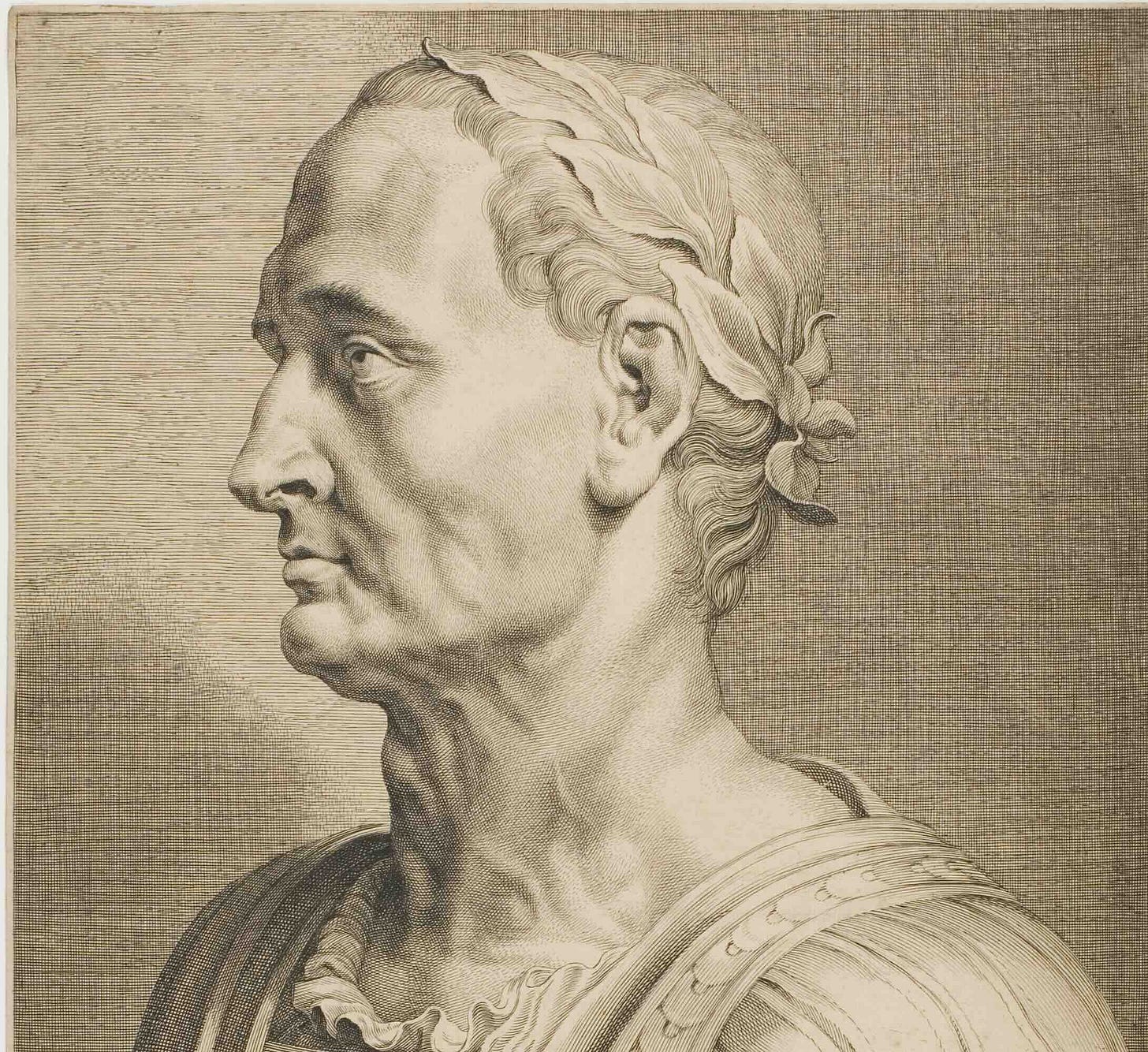

There is no “we, the people” or “rule of law” in tyranny. Rather, the tyrant imposes his will as an act of self-assertion. As the tyrant Creon says in Sophocles’ Antigone, “The law rules; but I decide the law.” Or consider Julius Caesar. He defied the Senate when he crossed the Rubicon. And he spoke of power in the first person, saying, “I came. I saw. I conquered.”

The grammar of tyranny is pre-modern and un-American. Thomas Jefferson explained, “Law is often but the tyrant’s will, and always so when it violates the right of an individual.” And the American libertarian author Lysander Spooner warned, “The single despot stands out in the face of all men, and says: I am the State: My will is law: I am your master.”

The Trumpian “I”

One of Donald Trump’s linguistic quirks is his tendency to speak in the first person when talking about matters of state. Trump often talks as if he alone controls the nation and decides the fate of the world. In a notorious recent interview with the New York Times Trump said that the only thing that limits him is, “My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.”

Consider Trump’s remarks about invading Greenland at the World Economic Forum in Davos:

We probably won’t get anything unless I decide to use excessive strength and force, where we would be, frankly, unstoppable. But I won’t do that. Okay? Now everyone’s saying, ‘Oh, good.’ That’s probably the biggest statement I made, because people thought I would use force. But I don’t have to use force. I don’t want to use force. I won’t use force.

People were relieved to hear Trump say “I won’t use force.” But the autocratic grammar is disturbingly capricious. Apparently, the President simply decides this stuff, without consulting Congress. Perhaps a few sycophants whisper in his ear. But decisions of global import are a matter of his mercurial will.

Consider, for example, how tariffs on foreign nations come and go according to the President’s mood. He explained recently that tariffs imposed on Switzerland were the result of a testy conversation he had with Switzerland’s president. He said, “She just rubbed me the wrong way.”

This first-person linguistic habit is linked to Trump’s jokes about being a dictator. After his official Davos speech, Trump spoke to members of the ruling elite, bragging about how much he has benefited the oligarchic class. That’s where he said, “Sometimes you need a dictator.”

He seemed to imply that this was all a joke. But Thomas Jefferson would not be laughing.

A Smug Savior

Perhaps Trump fancies himself a benevolent despot. He explains his fantasy about the Nobel Peace Prize by appealing to his own benevolent power. At a recent press conference, the President bragged about saving millions of lives by resolving wars across the globe. He said, “I saved millions and millions of people… I saved probably tens of millions of lives in the wars.” And, “I saved millions of people. So that, to me, is the big thing.”

It is absurdly grandiose to claim that he alone saved millions of people. And it is terrifying to think that the lives of millions depend upon his benevolent will.

Trump appears to believe a self-aggrandizing narrative in which he is kind of savior. In his January 2025 inauguration speech, the President said (referring to a failed assassination attempt), “My life was saved for a reason. I was saved by God to make America great again.” He has repeated this point several times, including in a speech to a joint session of Congress in March, 2025.

The same theme appears in a notorious tweet from early 2025: “He who saves his country does not violate any law.”

Trump is clearly fascinated with his own power. He often brags about how he imposes his will on the world. For example, in a rambling press conference, the President joked about renaming the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of Trump.

I was going to call it the Gulf of Trump, but I thought that I would be killed if I did that. I wanted to do it. I wanted to… I’m joking, you know, when I say that… The Gulf of Trump, that does have a good ring, though. Maybe we could do that. It’s not too late.

Trump is intoxicated with his power to name things after himself, as I argued in another column. Even if the Gulf of Trump idea is as much of a joke as his claim about being a dictator, these wisecracks disclose the smug hubris of Trump’s tyrannical “I.”

The Alarming Hubris of the Tyrannical I

It’s frighteningly absurd that decisions of global import are subject to the President’s hubristic whims. Sophocles warned that it is hubris that breeds the tyrant. The tyrannical “I” is hubris made manifest in grammar.

Several implications follow.

The tyrant’s “I” is supposed to be absolute. This means that those who oppose his will are guilty of treason. As Creon explains in Antigone, “Disobedience is the worst of evils.” This explains why Trump frequently accuses his opponents of treason, including Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, James Comey, and Mark Kelly. He conflates opposition to his will with treason to the state.

The tyrant’s “I” replaces reason with whim. Such puerile imperiousness is unmoored from reality. Tyrants make up their own facts because they can. The tyrannical manipulation of truth helps shore up the chaos generated by the tyrant’s arbitrary will. Consider for example, Trump’s absurd justification for renaming the Gulf of Mexico: “It’s the Gulf of America because we have 92 percent of the shoreline.” In truth, the U.S. has less than half of the coastline of the Gulf.

Not only is the tyrannical “I” divorced from truth but it is also untethered from the spirit of democracy. Our nation began with Americans denouncing the tyrannical and arbitrary will of King George in the Declaration of Independence. The Constitution’s separation of powers is supposed to limit the arbitrary caprice of the executive branch. Our government is supposed to be of the people, by the people, and for the people—not the willful imposition of one man’s mood.

Trump has not yet crossed the Rubicon. As I argued in my book on Trump and tyranny, our Constitutional system is strong enough to ensure that Trump remains merely a would-be tyrant, But under Trump, “we, the people” has increasingly become “me, myself, and I.”